Tino Rawa Trust – Crossing the Tasman Sea

August 21, 2023

Tom’s quest to row across the Pacific Ocean.

September 8, 2023

As the anticipation for the upcoming 2025 Australian Wooden Boat Festival steadily grows, we’ve embarked on a journey that spans oceans and cultures, uniting us with characters who share our passion. Our quest has brought us into contact with a diverse array of individuals who are as captivated by the allure of wooden boats as we are.

Yet amidst this captivating mosaic of tales and experiences, one narrative stands out in its uniqueness and intrigue—a story that unfolds along the shores of Bali, where the ancient art of boat-building is a living testament to tradition. Join us as we journey into the captivating world of the Jukung, a story from a man with a dream.

Thanks to Steve Roper for sharing his story, images and captivating videos.

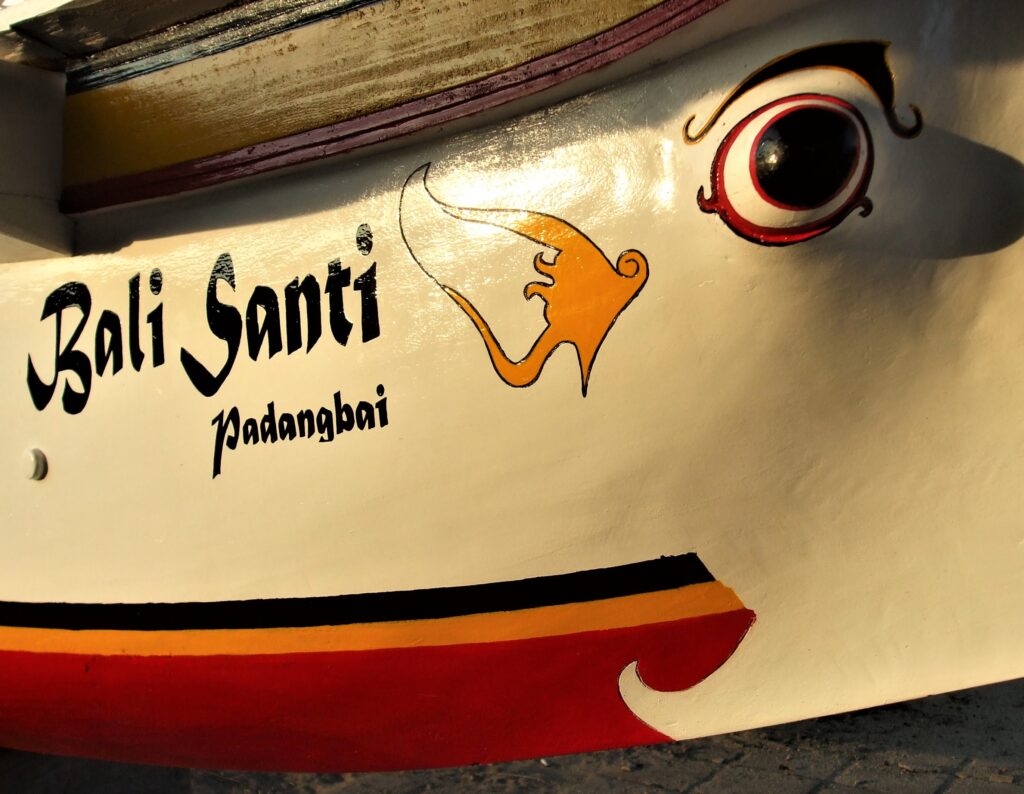

BALI SANTAI, THE STORY OF A JUKUNG [Balinese Double Outrigger Canoe]

Having visited Bali many times, I was struck with the beauty of the local fishing boats. Seeing the rapid change to the more utilitarian fibreglass, I decided to make a video documentation of this disappearing art form.

In 2012, having retired a few years earlier, I had the wherewithal for an extended stay in a Balinese village. However the common sight of local boat building had died out, so I decided to commission my own Jukung.

I was lucky enough to meet a master Jukung builder, Made Jawa, in the small port of Padangbai, on the south east coast of the island.

We travelled about 20 kms to Desa Ulakan, Karangasem, to select a suitable tree. Belalu [Albizzia falcata] was introduced to Bali, by the Dutch, and is the tree of choice.

On an auspicious day, usually in the wet season to reduce insect infestation, and according to the Balinese calendar, the 30 year old tree was cut down, after the limbs had been removed by a specialist, and then partially hollowed out by a chainsaw specialist, plus some handwork from Made.

Left to dry for one week in the jungle, it was then taken by truck to Padangbai and dried for a further four weeks.

The history of outrigger 5 part canoes, used by Austronesian people from Madagaska to Hawaii, goes back thousands of years. The 5 parts are the hull, two winged stem pieces and two gunwales.

The present style dates back about 70 years. Where as previously the parts were stitched together, epoxy resin and nylon rope have replaced natural materials.

The stem pieces, off cuts from the log, are fitted first, followed by planks for the gunwales, chainsawed from in side the hull. The main tools are a small handed axe and an adze with an adjustable head, thought to have originated a thousand years ago in what is now the Philippines.

Other modern metal tools, include a saw, spokeshave and brace and bit for inserting pegs before gluing.

A series of images of the build:

The Jukung is built on a system of numbers that gives the proportions for every part. The length is the inside measurement and divided into six. This marks the position for internal transverse supports and gives the placement and lashing points for the mast and rudder assembly.

Short flat transverse boards, with square holes, layang layang, for the mast, and penyankilang, for the rudder assembly, are let into the hull. These provide a base for the upwardly curving outrigger booms, banyungang. A pegged scarf joint connects the downwardly curving pieces, cedik, which connect to the bamboo floats, kantih. These assembly are lashed to the transverse hull braces, sendung.

The mast, outriggers, and other fittings are made from the locally growing Waru tree, Hibiscus tiliaceus, more commonly known as Sea Hibiscus. It was introduced to the region by Austronesian people as a source of timber and rope making from the bark.

The pronounced curves of the outriggers are found in areas surrounding the Lombk Straits, where rougher seas are encountered, and provide better clearance from larger waves.

The two boom triangular sail is supported, at its point of balance by a fixed rope from the top of the mast, tiang. The sail and upper boom, pembau, in this region are held upright by a kulkul which allows the toe of the boom to slide back and forth.

The only control ropes are a sheet to the lower boom, penggiling, and a sheet to the upper boom, pembau, which acts as a backstay. To tack, the booms rotate around the mast, and then the sail is also passed around.

The large size of the rudder, pancer, which can be easily removed, acts as a stern lee board that assist passage into the wind.

Finishing of the hull, is with a spokeshave and sandpaper, before painting. This is a relatively recent development and has considerably extended the life of the vessel. Though painted, the bamboo floats are often removed when not in use.

The distinctive eyes on the bow, which ward off evil spirits and guide the boat back to port, are part of the Gagah Minah, Elephant Fish, with large jaws and a tail. These pieces are also made from the original belalu log. The new fibreglass Jukungs have none of these iconic features.

The Jukung in Bali, though not recognised by tourists and most Balinese, is a valuable remnant of an Austronesian canoe tradition that has disappeared almost without trace from Pacific cultures.

Recommended reading, Outrigger Canoes of Bali and Madura, Indonesia by Adrian Horridge.

Library of Congress Catalogue Card No. 86-73058. ISBN 0-930897-20-X. ISSN 0067-6179.

For an in-depth video account of this project please Steve’s Youtube Channel here.

Want more stories like this, check out our past collection here.