Maritime Marketplace is Buoyant for 2021

May 16, 2020

The Australian Surfboat

May 21, 2020

Mabel, an early whaleboat-style fishing boat with tanned sails and a steering oar. She was wrecked at Bruny Island in 1895, with the loss of one of her crew of two. -Jonothan Davis Collection

Tasmanian Fishing Boats: A Brief History

—– By Graeme Broxam

Every AWBF brings together the tools of trade of one of Tasmania’s earliest and most important industries: fishing. The island is rightly famous for its marine life, with numerous commercial species including sharks and scale fish of diverse types, crustaceans such as the “crayfish” or rock lobster, and shell fishing such as oysters, scallops and abalone. Species tend to come in and sometimes out of favour at different periods, and different types of boats are developed or modified to exploit the fisheries. This article will, with inevitable over-simplification, discuss the development of the Tasmanian fishing boat up to the 1950s.

Early Fishing Boats

Until the mid-nineteenth century most Tasmanian fishing boats were quite small. At Hobart Regattas in the 1840s local fishing boats competed as four-oared rowing boats, although when working they probably carried a dipping lug sail like other contemporary workboats, the whaleboat and the waterman’s gig or wherry. As a rule-of-thumb, four-oared whaleboats (and the larger class of waterman’s boats) were about 25 ft long, while the five and six-oared bona fide whaleboats used on whaling ships and in bay whaling trade were about 28-30 ft. Many of the latter are believed to have been converted into fishing boats once their whaling days were over.

The early fishing vessels seem to have been mostly two-man boats that worked under sail and oar, without wet-wells, seeking catches within an easy sail of the market. The crew of a fishing boat seen lurking about Tinderbox in May 1839 were suspected of stealing four hundred-weight of potatoes from Joshua Ferguson’s farm – an event which implies something about both the size of the boat and the repute of the fishermen, who Ferguson accused of further petty thievery in 1840.

Larger vessels appeared from time to time, such as the Colonial Government’s 15-ton schooner Rambler that operated as a fishing boat on the Derwent in 1831-32, much to the dismay of the anti-government press. Over the years a number of Deep Sea Fishing Companies were proposed: perhaps the only one that went much past the public meeting stage, based in Launceston, built a 16-ton cutter Dolphin to work off the east coast in 1834, but it soon folded after the drowning of the boat’s skipper and one of the crew of two in a boating accident at George’s Rocks.

The dangerous nature of the Tasmanian coastline was and indeed continues to wreak havoc amongst Tasmanian fishing craft. Shipwreck claimed two of the first large vessels with wet-wells to fish in Bass Strait: the Melbourne-based 13-ton cutter Pomona took cod off King Island and crayfish off the far NW Coast before parting from her moorings at Robbins Island and being wrecked in 1856, and her replacement the much larger 45-ton former Dogger Bank smack Ebenezer did almost exactly the same thing in 1859. A similar fate befell Hobart’s first deep-sea trawler, William Bennett’s 35-ton schooner Alfred and Jacob, wrecked on the Tasman Peninsula in 1856.

Fishing Boats 1860-1900

During her brief career as a trawler, on one trip east of Maria Island the Alfred and Jacob took six tons of fish including trumpeter, perch, barracouta, rock cod, gurnet, and a 70-pound New Zealand cod. Her loss didn’t hold back the resourceful William Bennett, as he went on to become the true pioneer of offshore fishing in southern and south-western Tasmania. In the early 1860s he built three large “whaleboat” type fishing boats to work off the West Coast, the Alert, the 42 ft Frolic and 47 ft Flying Cloud. They were followed by other large boats such as David Wilson’s 42 ft Matilda in 1867 and 43 ft Colleen Bawn in 1871. Wilson’s Matilda was wrecked in 1881 but a smaller 40 ft Matilda built about 1892 for the Moody Brothers survives as perhaps the last Tasmanian colonial-era purpose-built sea-going fishing boat.

In Hobart River Craft, Harry O’May described the typical inshore fishing boat as being about 28 ft long with a beam of 5½ to 6 ft, which is again consistent with a ship’s 5-oared whaleboat, at least at the lower limit of beam. They were rigged with a spritsail and jib, often tanned red with wattle bark. They were steered with either rudder or steer oar, and fished using seines or graballs. Being at best “half-decked”, accommodation was rudimentary and just about the only creature comfort was a fire-pot for both cooking and heating at night, under a tent contrived from the mainsail.

A smaller type of fishing boat, generally 18-24 ft, was popular in the harbours leading into Bass Strait. They tended to be clinker or sometimes batten-seam carvel boats not dissimilar in concept to the well-known Queenscliffe couta boat, generally fitted with a small well. With a certain degree of evolution, especially after the internal combustion engine became readily available, they continued to be built into the 1950s. Those built on the Tamar were known as “cod boats”. The earliest surviving Tasmanian fishing boat list is from Strahan in 1903: about 40 small fishing boats were licensed for use on Macquarie Harbour between then and the 1920s: at least one of these, the 22 ft Florence apparently built in the mid-1890s, is still in existence at George Town. Small fleets of such boats could be found in just about every harbour in Tasmania, and in total numbered many hundreds.

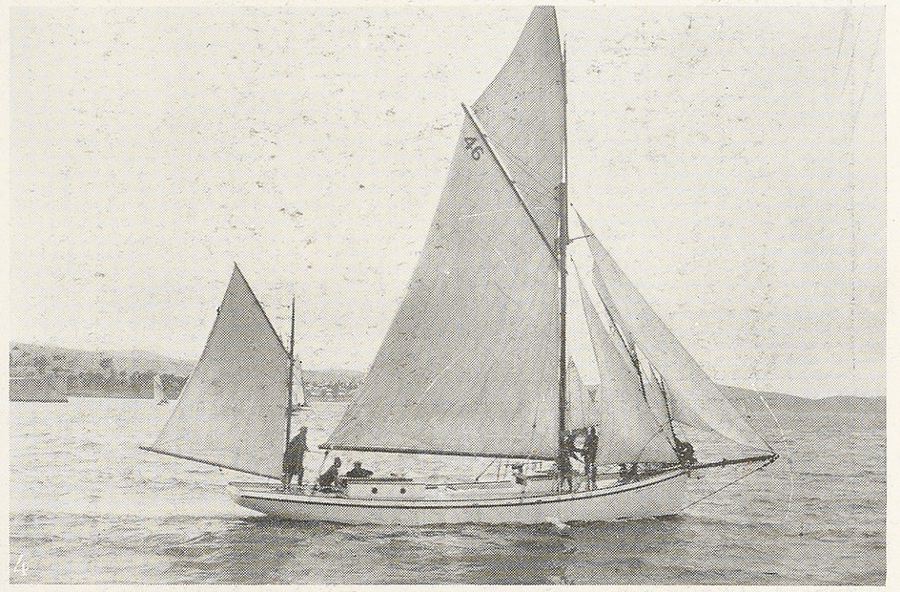

-Graeme Broxam Collection

The larger offshore fishing boat of the type pioneered by the likes of Bennett and Wilson were merely larger descendants of the smaller whaleboat-type fishing boat. They were generally in the range 34-42 ft in length, about 7-11 ft beam and generally with no more than 4 ft depth of hold. Construction was generally batten-seam carvel from Huon pine on hardwood keel, stem and stern and with steam-bent blackwood ribs. Rig was generally gaff cutter, ketch or yawl, the latter where a shallow counter stern was built aft of the stern post. They often had two or three clinker planks on the topsides, which tended to strengthen the lightweight hull, while, according to legend at least, avoiding the sharp slap of water against clinker planking that would have warned the fish. This practice may have evolved from building up the topsides of carvel-built former whaleboats for use as fishing boat.

Many of these nineteenth century vessels were, other than the well, indistinguishable from the smaller trading craft in the firewood and produce trades that were known as “passage boats” (after the “southern passage” or D’Entrecasteaux Channel, where many traded), and many such boats swapped regularly trades. Indeed, as steamers took over much of the cargo trade once maintained by small sail traders, many of the former river and inshore coastal trading ketches including many well-known craft like Fancy, Gertrude Lucy, Ruby Louise, Lenna (I), Alice and Agnes (later Olive May) and Forget-Me-Not were converted into fishing vessels: of these Olive May(1880) and Fancy (1885) still exist. When road transport took away the trade of the river steamers, some of those also ended up as fishing boats. Many small yachts, especially those of the 21-foot waterline and 28-foot waterline categories, also joined the fishing fleet once they were superseded. Most of these boats were still primarily chasing scale fish but from time to time other species were caught, such as sharks that were converted into fertilizer.

-Graeme Broxam Collection

At the larger end of the later 1800s/early 1900s fishing trade were vessels superficially similar to the smaller coastal trading ketches, like the 52 ft Rachel Thompson built in 1877. This vessel was at first mostly involved with scale fishing off the East Coast and was large enough to take loads of fish to Melbourne and Sydney. This type of vessel became more common in the early 1900s as demand for crayfish increased in Melbourne and Sydney. Many large boats of this type were built for the trade, the best-known family being the Burgesses then based in Melbourne. Their last purpose-built fishing ketch Julie Burgess built at Launceston by E. A. Jack 1936 is still sailing out of Devonport. Many former trading ketches also ended up in the fishing industry, the last of which, Birngana, was only wrecked as late as 1987.

Fishing Boats 1900-1950s

In 1900 Charles Lucas built at Battery Point a revolutionary new fishing boat that the contemporary press decided ought to be called a “fishing yacht”, from the quality of her appearance and appointments. This was the 43 ft Blanche designed by Hobart’s best-known yacht designer, Alfred Blore. Blore took most of his concepts from overseas yachting magazines and it would seem no coincidence that the hull lines of the Blanche were reminiscent of American cruising yawls of the period.

This development was soon followed by the internal combustion engine. The first motor fishing vessel operating in Tasmanian waters was probably the 42 ft Frolic out of Melbourne in 1899 (she become a Hobart boat in 1908, and some 113 years later she is still sailing as a yacht). In January 1904 the traditional double-ender Lucy Adelaide was fitted with an oil engine; and later the same year the purpose-built auxiliary fishing boat Britannia, a modern style boat with a counter stern, also entered service.

By 1910 several auxiliary fishing cutters and yawls had been built or were under construction: notable examples operating out of Hobart and still in existence are Aone and Curlew. Many were built in the south by such well-known builders as Charles Lucas, Purdon & Featherstone and Percy Coverdale of Battery Point, C. H. Mackay at Woodbridge and the Wilsons of Port Cygnet, but several were also built in the north of the state, most notably by E. A. Jack in Launceston. They filled just about every segment of the industry, especially the burgeoning crayfishing industry, which had lapsed into something of a cottage industry since the 1850s.

Regular, fast steam ship services to the mainland in the early 1900s made the export of fresh fish a possibility, and one of those who took advantage of this was Captain Spaulding of Dunalley. Boats owned by himself and associates caught their crayfish up the length of the East Coast, transhipped them at Dunalley for Hobart by river steamer, and they mostly went to Sydney. Some very fine fishing vessels that are still afloat over a century later were built for this trade, including D.J.V., Lalla Belle and Casilda. Fully-decked vessels with raised coach-house forward and cabin aft for the engine, these boats were quite luxurious compared to their predecessors, and contemporary fisherman William McKillop waxes almost lyrical on them in his memoirs recently published The Last of the Sail Whalers. They were capable of lengthy passages, and some took crayfish direct to Melbourne from the Tasmanian NE coast. An even bigger vessel of this type is the 54 ft cutter Storm Bay built in 1925 for poling barracouta in waterway for which she is named.

The increasing growth in scallop fishing after 1910 encouraged many owners of old double-ended boats to put square counter sterns on them to support and work the dredge. Some like Matilda and Fancy gained little more than rudimentary platforms, while the Olive May underwent a more radical transformation where her former whaleboat stern was opened out to form an elegant fantail counter.

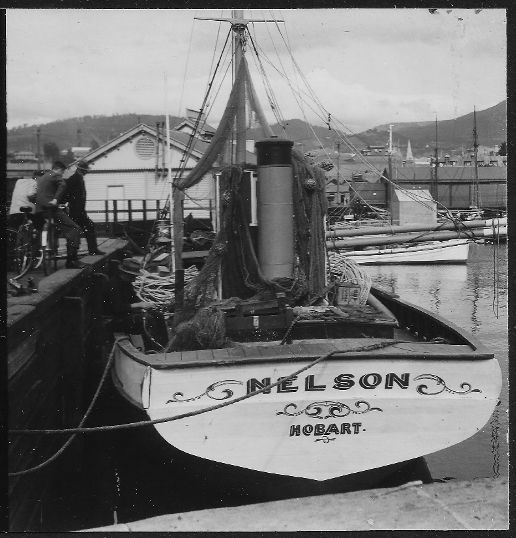

Improvements in diesel engines mid-century saw them become a principal form or propulsion rather than merely auxiliary to sail. The transition encouraged beefier hulls that could be forced through heavy seas in most weather, rather than the fine lines required for a sailing vessel to have a hope of getting where its crew wanted in a reliable manner. Many transitional auxiliary fishing boats from the 1940s still survive, like Jean Nichols, Kerrawyn, Stormalong and Rhona H the first two built by Wilsons at Port Cygnet, and the latter by E. A. Jack in Launceston. Although Hobart’s first full-powered motor trawler, the Nelson, was built in 1937, such types of boats did not become common-place until the 1950s. A large number of such vessels still survive, some still as commercial fishing vessels, others as pleasure craft, and will undoubtedly be represented at AWBF 2021.

-Graeme Broxam

-Graeme Broxam Collection

References:

Broxam, Graeme, Those That Survive: Vintage & Veteran Boats of Tasmania, Navarine Publishing, Canberra, 1996.

Broxam, Graeme and Nash, Michael, Tasmanian Shipwrecks, Volume One 1797-1899 (3rd Edn.), Navarine Publishing, Hobart, 2020.

Kerr, Garry, Craft and Craftsmen of Australian Fishing 1870-1970: An Illustrated Oral History, Mains’l Books, Portland, Victoria, 1985.

McKillop, William, The Last of the sail Whalers: Whaling off Tasmanian and Southern New Zealand, edited by Rhys Richards and Graeme Broxam, Navarine Publishing, Hobart, 2019.

National Library of Australia, TROVE Online Australian Newspaper Database 1803-1954.

O’May, Harry, Hobart River Craft and Sealers of Bass Strait, Government Printer, 1973 reprint.